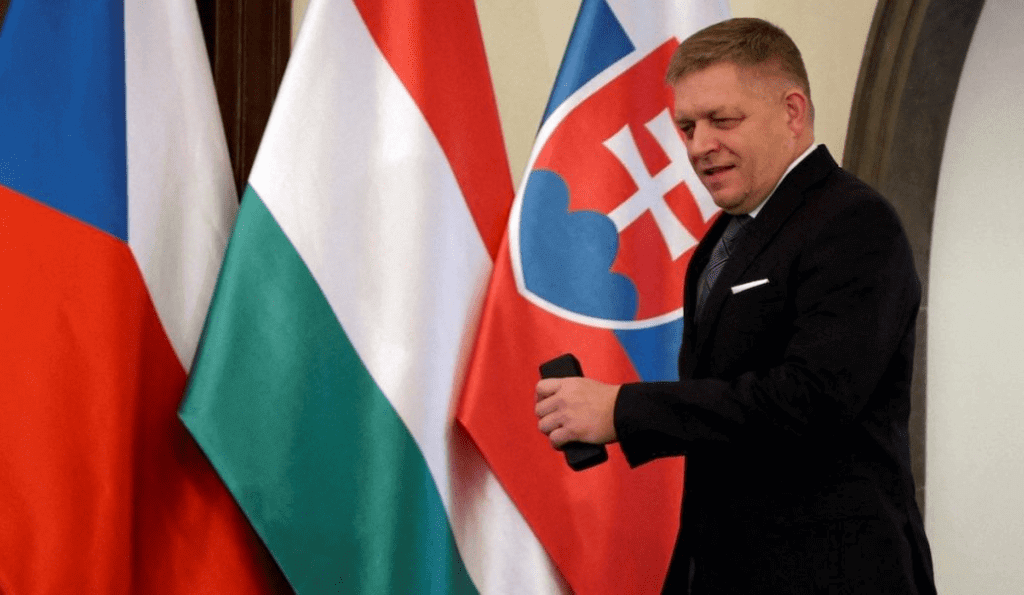

Under Prime Minister Robert Fico, the Slovak government reportedly recently acquired spyware similar to Pegasus, capable of infiltrating mobile phones and gaining full access. Once inside a phone, the spyware can extract data from its microphone, camera, and screen. It can even download app content, including from encrypted platforms like Signal. This sophisticated tool can infect the phone remotely, requires no user interaction, making it nearly impossible to prevent infiltration.

Human rights organizations such as Article19 expressed grave concern over this development, and in particular over the fact that Slovakia’s spyware acquisition came as the Fico government worsened democratic and human rights conditions in Slovakia. Article19 also highlighted “the historical context of Pegasus’s use” in surveilling “journalists, human rights activists, and political dissenters” in European and other countries.

The original report on Slovakia’s spyware acquisition came from Denník N, which cited opposition MP and security and defense expert Juraj Krúpa (Freedom and Solidarity party; SaS) as one of their sources. Denník N also claimed to have confirmed the Fico government’s spyware purchase from four additional sources close to the Slovak security community.

When asked by VSquare, Krúpa himself confirmed receiving consistent information on the surveillance tool acquisition from three independent sources (it is unclear if Denník N and Krúpa’s sources overlap). These sources told the opposition MP that the Slovak Information Service (SIS) has been trying to get their hands on the “latest version” of spyware similar to Pegasus for a long time. After negotiations, the spyware supposedly went through a testing period over the summer before it was finally deployed in September. “I’m aware that some opposition politicians and journalists are being targeted [with surveillance], and they are attempting to dig up compromising information on them,” Krúpa told VSquare.

Meanwhile, the Slovak government denies these reports. However, it is worth recalling that, after Hungary’s and Poland’s abuse of Pegasus came to light, their governments denied using it, too.

How is such spyware operating in Slovakia?

The most famous spyware of recent years, Pegasus, is manufactured and sold by NSO Group, an Israeli company. The private firm was established by former Israeli intelligence officers. Access to the software has been political, too: the spyware’s export licenses are approved by the Israeli Ministry of Defense. The name of the spyware being used in Slovakia is not yet known, nor is the company behind it. However, Krúpa’s sources identified it as an Israeli firm. Besides Pegasus and NSO Group, there is another Israeli spyware company – Predator, developed by Cytrox/Intellexa – that was identified as being connected to the surveillance of journalists and opposition politicians in Europe in recent years.

The possession of such spyware by EU countries’ governments seems to be widespread. The European Parliament Committee of Inquiry, meant to investigate the use of Pegasus and equivalent surveillance spyware (PEGA Committee), concluded in 2023 that the majority of EU member states have purchased some kind of spyware. However, these tools are frequently misused and applied to the surveillance of journalists, political opposition figures and activists, which is why civil society has been critical of spyware purchases.

According to Krúpa, Slovakia’s SIS does not own the system that operates the recently purchased spyware. Instead, they are paying per each device that is surveilled. Generally, spyware technologies work on a similar subscription or service basis, whereby a select number of targets are under surveillance for a specific period, for which the tool is then operated by the spyware company. Krúpa also told VSquare that the acquisition of this tool did not require approval from the Slovak parliament or its special oversight committee, which exists to monitor SIS and remain abreast of national security matters.

Previous leaks had already revealed that Slovakia has certain spyware. For example, documents published on WikiLeaks in 2014 showed that Slovakia purchased the FinFisher spyware, developed by Gamma Group. This was followed by a leak of communication between Slovak intelligence and the Italian Hacking Team company over the possible purchase of the company’s Galileo software. Neither of these purchases were officially confirmed. In 2021, Slovak military intelligence stated that they did not use this system, but SIS, refused to comment.

Krúpa further discussed the SIS’s alleged ability to surveil devices without a court order because of a lack of oversight mechanisms, especially with a new spyware. According to his information, within the Slovak national security apparatus, only SIS has access to the spyware. According to the law, there are, in theory, five organizations that have the right to carry out surveillance in general: the police force, the Slovak Information Service, military intelligence, the Corps of Prison and Judicial Guards, and the customs administration.

However, in the current Slovak Penal Code, the use of surveillance is approved under specific conditions, and surveillance without a court order is only allowed in critical situations. Even in this case, the court needs to be contacted within one hour after beginning surveillance.

Fico’s government denies everything

As was the case following previous leaks over Slovakia’s acquisition of spyware, SIS refused to comment on recent reports, arguing that the confidentiality of all their operations does not allow them to share any information publicly. They added that, if the potential spyware is used for the intended purpose of uncovering illegal activities, sharing any details could hinder investigations.

Both Minister of Interior Matúš Šutaj Eštok (Hlas) and Minister of Defense Robert Kaliňák (Smer-SD) denied the purchase of the reported spyware. They claimed such a purchase would have been impossible because Slovak law prohibits such technology. “No Pegasus. On the contrary, in the case of this ‘worm,’ we have to approve legislation that will prevent it, because it would really be an invasion of privacy if such a system existed [in Slovakia],” Prime Minister Robert Fico stated at a press conference after a party meeting. However, Fico’s carefully chosen words about future legislation banning Pegasus led to speculation that his government obtained not Pegasus, but some other spyware.

Matúš Harkabus, a former prosecutor at the Special Prosecutor’s Office, which no longer exists as it was shut down by Fico’s government earlier this year, explained in a Facebook post that the use of similar spyware is entirely possible under current Slovak laws. For now, many questions remain unanswered, including regarding the direction of new legislation in Slovakia on the functioning of potential surveillance methods – or the complete ban of Pegasus, as suggested by government members.

There is one body that could provide answers to these questions, at least in theory: the Slovak parliament’s special committee overseeing SIS activities. However, this committee had an eventful summer, which culminated in the removal of its opposition chair, Mária Kolíková, on June 27. Without a chair, the committee cannot hold meetings, thus making the committee non-functioning. On September 17, 2024, a new chairman was appointed from within the ruling coalition, Samuel Migaľ (Smer-SD). This development was announced at a press conference, where Migaľ appeared alongside SIS director Pavol Gašpar and his father, Tibor Gašpar. The older Gašpar is currently the new vice-speaker of the parliament. In the previous Fico government, he was Slovakia’s police chief, a role he conducted in such a way that he is now facing multiple investigations and charges, including for alleged bribery and organized crime. Initially, Fico wanted the elder Gašpar to lead SIS, but he eventually settled for his son.

While coalition and opposition parties agree that the oversight committee’s chair needs to be an MP from the opposition, the ruling majority refused to approve Kolíková for another term, claiming that she “harmed the reputation” of SIS. During her tenure, Kolíková started scrutinizing how regulation around SIS had been changed, suspecting that these changes had been made to help the untransparent appointment of a new director avoid scrutiny.

Following Poland and Hungary’s example

While opposition MP Juraj Krúpa lacked precise information on the cost of the spyware, he estimated that the price could amount to millions of euros. Since the Fico government recently purchased a BARAK MX Israeli air defense system for €554 million, there is now speculation that it might have come as part of a package deal along with Israeli spyware. Krúpa could not tell VSquare whether the purchase of Israeli spyware happened directly or through an intermediary, as was the case in Hungary.

Hungary was the first EU country hit by the Pegasus spyware scandal. In 2021, an international investigation dubbed the “Pegasus Project” found more than 300 Hungarian telephone numbers in a leaked database of more than 50,000 numbers, all of which had allegedly been targeted by NSO Group’s international customers using Pegasus. Among the Hungarian numbers were those of journalists working for independent outlets (including journalists from Direkt36, VSquare’s Hungarian partner center), lawyers, politicians and businessmen who owned media critical of Viktor Orbán’s government. Hungary’s government initially refused to acknowledge the purchase of the spyware, or to cooperate with the European Parliament inquiry committee investigating spyware abuses. Later, Direkt36 also found the intermediary company that purchased the Pegasus spyware for Hungarian intelligence for around €6 million.

In Poland, the story was almost the same. Polish journalist Michał Kokot, an author of a book about the Pegasus surveillance scandal in Poland, told VSquare that, in December 2021, the reaction from the Law and Justice (PiS) government was very similar to that of Kaliňák, Šutaj Eštok and Fico – that is, they simply denied having obtained the Pegasus spyware.

“They did it for weeks until [PiS leader Jaroslaw] Kaczyński in early 2022 confirmed that such a system exists,” said Kokot. But even then, ruling party politicians claimed that the operation of the Pegasus system in Poland served only criminal, and not political, purposes. It was only when the case of Krzysztof Brejza came to light that it became clear how untrue that claim was. Brejza was the manager of the opposition’s campaign in 2019, when PiS surveilled him, his father and his assistant under a criminal pretext,” Kokot added.

It was only after the Polish parliamentary elections in 2023, when PiS was defeated by the Donald Tusk-led coalition of democratic parties, that it was possible to start a proper investigation, which is still underway.

“They [the Tusk government] face massive problems with getting access to the information from the services, officially due to security reasons. Part of their findings, the most interesting ones, will be classified and not open to the public,” Kokot said. He doesn’t believe that the Polish public will receive answers in the foreseeable future on whether the system was bought for political or professional reasons. “One thing is sure: the misuse of Pegasus led to a ban from the Israeli producer NSO. The Polish services lost a great tool, which made it possible for them to obtain encrypted messages and calls remotely from devices of the suspects. They and the prosecutors miss it a lot,” the journalist said.

Kokot referred to reports following the Pegasus surveillance scandals in Poland and Hungary. These reports claimed that NSO Group terminated the contracts with two unnamed clients from within the European Union, which was widely believed – but never officially confirmed – to be these two countries.

Meanwhile, European NGOs want to prohibit the use of Pegasus and similar spyware everywhere in the EU. The regulation or ban of spyware on EU level has been a discussion point since 2021 and revelations around the Pegasus Project, which made clear the wide scale abuse of this technology on the continent. But as a reaction to subsequent findings of the European Parliament’s PEGA Committee and criticism of the insufficient powers and unenforceable nature of the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA), a coalition of civil society organizations is asking EU institutions for more substantial changes. Among the requests are a new EU legal framework, and until that is in place, a moratorium on spyware purchases, spyware development, and checks on compliance of member states.

Read More: https://vsquare.org/slovakia-robert-fico-pegasus-spying-human-rights/

Source Credit: https://vsquare.org/